I was working out at the gym when I spotted a sweet young thing walking in…

I asked the trainer standing next to me, “What machine should I use to impress that lady over there?”

The trainer looked me over and said; “I would recommend the ATM in the lobby.

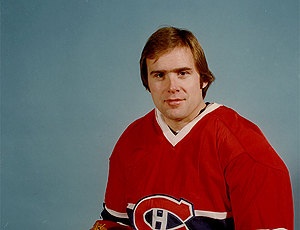

Thirty Years Later, Ken Dryden Updates ‘The Game’

By JEFF Z. KLEIN

Since it was published in 1983, “The Game,” Ken Dryden’s memoir and extended meditation on goaltending, hockey, family and life with the dynastic Montreal Canadiens, has justly earned a reputation as the best book written about the sport, and perhaps any sport, in the English language. That high opinion has been expressed often over the years, by sources as diverse as Mordecai Richler, Sports Illustrated, Alan Thicke, the CBC and Bill Simmons.

“The Game” has been republished in a 30th anniversary edition by HarperCollins in Canada and Triumph Books in the United States (Simmons wrote the new edition’s foreword), and it remains as much a revelation on a second reading as it was on the first.

Larry Robinson, Serge Savard, Bob Gainey, Scotty Bowman and the rest of the great Habs teams that Dryden backstopped on the way to six Stanley Cups live as vividly in these pages today as they did when Dryden first put them there so long ago: Réjean Houle, haunted by a poor childhood, “wheeling for nickels and dimes like a French Canadian Sammy Glick”; Guy Lapointe, continually playing practical jokes and eliciting the exasperated cry from teammates: “Pointu!”; Guy Lafleur, the elegant Flower, speaking of the primacy of hockey over family “with the tone of a contented victim, resigned to the future he wants,” and in so doing, “merely expressing the reality of most career-directed, cause-directed men.”

Dryden wrote “The Game” in his last season as a player before retiring at the tender age of 31; it is remarkable that a writer that young could be so eloquent on his first try as an author, given that he was usually otherwise engaged, stopping pucks. But he was known as a thoughtful guy — he had taken a year off from the Canadiens to complete his law degree at McGill University. And, sure enough, after retirement he embarked on a peripatetic career as a thinker and doer.

Dryden wrote more books, on subjects like hockey, education and Canada’s place in the world. He served as president of the Toronto Maple Leafs for six years and as Ontario’s youth commissioner for two. He was elected to federal Parliament and served seven years, and at one point ran, unsuccessfully, for the leadership of the Liberal Party. After losing his seat in Parliament in 2011, he became a forceful voice for reforms aimed at reducing head injuries in hockey.

But “The Game” remains Dryden’s signature achievement. For the anniversary edition he wrote a new closing chapter. When he played, the custom of allowing N.H.L. championship players to spend a day with the Stanley Cup had not yet been established. But in 2011 Dryden, as a former Cup winner, persuaded the Hockey Hall of Fame to allow him to take the Cup to his father’s tiny hometown, Domain, Manitoba, on what happened to be the 100th anniversary of his father’s birth. The next day he took the Cup to his own hometown, Etobicoke, a former municipality that is now a part of Toronto. There, in the backyard of his childhood home, he staged an all-day ball hockey game with his brother, Dave, who also played goal in the N.H.L.; all their childhood friends and minor hockey teammates; and all the neighborhood children who showed up.

On a recent visit to New York, Dryden talked about “The Game” and those special two days in Domain and Etobicoke.

“What a day with the Cup is really for is the chance to say thanks,” said Dryden, 66 and still seeming taller than 6 feet 4 inches, as he did when he played goal. “That’s the magic of it. You have this candy store option: ‘You have a day — how do you want to spend it? Where do you want to be? Is home where you want to be?’ You know those things pretty well when you’re 27 and you win the Cup. But you know them as well as you’re going to know them when you’re that much older.”

Dryden said he knew where that place would be.

“The central hockey experience for me, even more than the Montreal Forum or any other place, was the backyard,” he said. “So much of the game, and the spirit of the game, is the everywhereness. It is the local rink in Etobicoke or in Domain, but it is the game as it is played where no rink has any chance to exist.”

Dryden chatted for another hour about the concussion epidemic in hockey and the lawsuit brought by former N.H.L. players; the relentless speed of contemporary hockey; the speed of the French Connection era Buffalo Sabres and why they always gave the Canadiens trouble; and the ins and outs of the writing business. He was contemplative — the product of a thoughtful mind coupled with the watchfulness of a skilled goaltender.

It is a quality that resonates throughout “The Game,” and it makes it an engrossing read, even today. Consider this passage describing the evanescent fading of Robinson’s prodigious skills. First, Dryden speaks of Robinson as a defenseman whose greatness “had to do with what he did and what he didn’t have to do because of how he did it.” But now that greatness has started to shimmer out.

“Close your eyes and think of Robinson again: his size, his occasional body checks and fights — these images still come quickly, but they are no longer features of his game. Try again. What do you see now? What is the instant image you get? What is the focus around which everything finds its order and purpose? What is the quintessential Robinson? I see an imposing, erect figure, the puck on his stick, moving slowly to center, others bent double at the waist skittering around him. Then, as if jerked into fast forward, the image speeds up: defensive corners, offensive corners, their net, our net, faster and faster, no pattern, like a swarming, sprawling force; everything blurred and out of focus. It happens every time I try it. I can see Lapointe; I can see Brad Park and Savard; I can see Denis Potvin’s crisp pass, his unseen move to the slot, his quick, hard wrist-shot. But I can’t see Robinson.”

It does not at all matter that Dryden painted this picture 30 years ago, of a player long since retired. To put it in a way Dryden would never do: they don’t write ‘em like that anymore.

There are 22 players in the NHL who are 5’9″ or shorter.

Eighteen of them play in the Eastern Conference. Five are Canadiens: Gallagher, Gionta, Daniel Brière, David Desharnais and Francis Bouillon.

There are more short players on this team than in THE ENTIRE WESTERN CONFERENCE.

Have a good weekend.

See you Sunday.

Peace.